On Dec. 7, 1941, more than 350 Japanese fighter planes attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, killing about 2,400 people—and igniting a near-hysterical hatred in America of all things Japanese. Two months later, in February 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued an executive order permitting the U.S. Army to remove any individuals from the general population who might be suspected of aiding the new enemy.

By year’s end, more than 110,000 men, women and children of Japanese ancestry had been rousted from their homes, crowded into railroad cars and carried inland from the West Coast to hastily constructed internment camps—euphemistically referred to as “relocation centers”—where they were kept under armed guard.

More than two-thirds of those imprisoned were American citizens. Some had sons serving in the U.S. Army. Regardless, they were all considered potential spies and saboteurs. “A Jap’s a Jap,” Lt. Gen. John De Witt said at the time.

Witt said at the time.

Harold Ickes, Roosevelt’s secretary of the interior, was appalled by the developments. In 1942, he reported to the president that conditions in some of the camps were brutal. “The result,” Ickes wrote, “has been the gradual turning of thousands of well-meaning and loyal Japanese into angry prisoners.”

Ickes sought a way to help correct what he regarded as a terrible—and unconstitutional—injustice. “I do not like the idea of loyal citizens, no matter of what race or color, being kept in relocation centers any longer than need be,” Ickes said. He argued that their skills should be put to good use, particularly given the manpower lost by the war effort. “We need competent farm help badly,” Ickes said.

Roosevelt relented, and in April 1943 Ickes arranged to have seven internees released from an Arizona camp and brought to Montgomery County. There, they were put to work on Ickes’ 65-acre Headwaters Farm, near the intersection of Georgia Avenue and Route 108 in Olney, as well as on the farm of his friend, former Washington Senators baseball player Sam Rice.

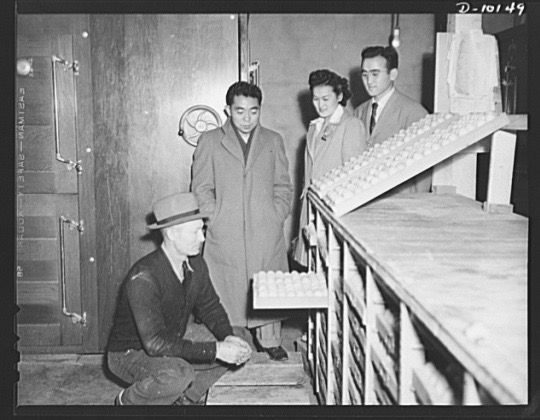

Three of the transported men were brothers. Fred, Roy and William Kobayashi were graduates of California State Polytechnic University and poultry specialists, a boon to Rice, whose farm off New Hampshire Avenue south of Ashton held more than 20,000 chickens. Ickes and Rice paid the workers $50 per month, plus room and board.

Other farmers around the region and eventually throughout the country saw the value in Ickes’ endeavor, and increasing numbers of Japanese-Americans were thus employed. In 1944, future poet laureate Carl Sandburg welcomed evacuees to his farm in Michigan.

Other farmers around the region and eventually throughout the country saw the value in Ickes’ endeavor, and increasing numbers of Japanese-Americans were thus employed. In 1944, future poet laureate Carl Sandburg welcomed evacuees to his farm in Michigan.

The relocation camps were finally disbanded in January 1945, eight months before Japan’s surrender. The released prisoners were given $25 and a train ticket home. Rice and Ickes had already negotiated the release of their internees, however.

William Kobayashi, his wife, Irene, and their son, Bill, remained on Rice’s farm. Fred Kobayashi left Ickes’ farm to become an instructor in Japanese wrestling at the University of Maryland and, despite his internment by the U.S. Army, later joined the service. His brother Roy moved to Toledo, Ohio, to work in a war plant.

In 1988, the U.S. government issued a formal apology for the internment, admitting that the action was rooted in racial prejudice and war hysteria. Eventually more than $1.6 billion in reparations would be disbursed to the formerly imprisoned and their heirs.

Discussion

No comments yet.