The Chevrolet Story

In 1911, automotive maker William Durant, the ousted founder of General Motors, teamed with famed Swiss racecar driver Louis Chevrolet to create a new car company. Durant named the enterprise after the racer, whose worldwide reputation, he surmised, would propel sales.

The hunch paid off, and by1916 Durant had become so wealthy that he bought a controlling interest in his old company — and Chevrolet became a division of GM.

Although well regarded for it high-end autos, it was Chevy’s smaller, less costly cars – direct competitors of Ford — that posted the stronger sales, and the company’s reputation became built on affordable value.

However, performance was not sacrificed for price, and Chevy’s early four- and six-cylinder engines – in the 1930s billed as “the cheapest six-cylinder car on sale” – became known for their speed and durability.

Chevy’s renown for performance went stratospheric in 1953 with the introduction of the Corvette – arguably the first American sports car. But it was the 1955 debut of its small-block V-8 that would presage a new era in affordable high-performance. For the next half-century the engine would power tens of millions of autos and trucks, its legacy passed on to succeeding generations of touring sedans, family wagons and performance cars.

By 1962, one third of all US cars bought in America was a Chevy – with domestic sales alone surpassing 2.3 million.

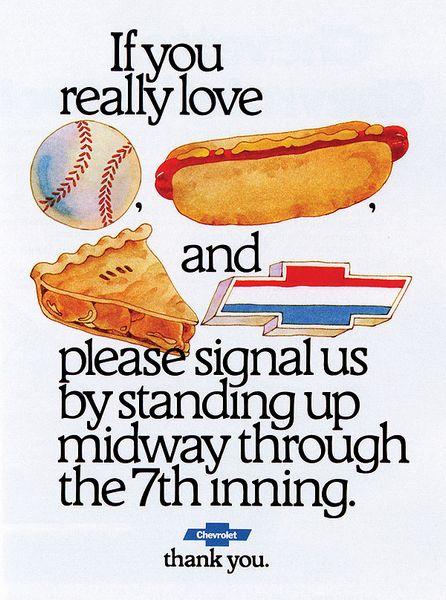

The Chevy Bowtie

The origins of the Chevrolet emblem – the “bowtie” – is shrouded in mystery. By one account, in 1908 Durant saw a pattern in the wallpaper of a French hotel and thought it would make a good nameplate for his new car company. By 1913, the emblem began to appear in Chevy advertisements.

In 1929, however, Durant’s daughter, Margery, claimed that the iconic emblem came from a dinnertime doodle. “I think it was between the soup and the fried chicken one night,” she said, “that he sketched out the design that is used on the Chevrolet car to this day.”

Meanwhile, Durant’s widow, Catherine, recalled how she and her husband were on holiday in Hot Springs, Virginia, in 1912, when he spotted a logo design for a local company and exclaimed, “I think this would be a very good emblem for the Chevrolet.”

Variations in color and detail have come and gone since the bowtie’s debut, but the shape has remained immediately recognizable.

In 2004, Chevrolet began to phase in the gold bowtie that today serves as its global brand identity.

Chevy’s Admen

On February 7, 1911, Frank Campbell and Henry Ewald, two Detroit-area admen with auto marketing backgrounds, formed a new agency, its focus apparent in its first tagline: ““We care not who makes the nation’s cars, if we may write and place the nation’s advertising.”

Six years later came their big break. General Motors vice president Alfred P. Sloan, Jr. called on the agency to create a campaign for the company’s nascent Chevrolet line. The first ads, appearing in 1917, touted how Chevrolet “meets completely the national need for dependable and economical transportation.”

Chevy took direct aim at Ford, which owned 50 percent of the market. Campbell-Ewald pushed Chevy’s combination of price and value with the tag, “The Economical Transportation.”

In 1927, Chevy’s annual sales surpassed Ford for the first time.

By 1929 – on the eve of the Great Depression — Campbell-Ewald operated in 13 cities, serving 100 clients, with billings reaching $26 million – more than $343 million in 2012 dollars.

Over the next eight decades, the agency would craft some of the world’s most memorable campaigns, with a parade of Chevy slogans entering the American lexicon: “See the USA in Your Chevrolet,” “Baseball, Hotdogs, Apple Pie and Chevrolet,” “Heartbeat of America,” “Like a Rock,” “An American Revolution.”

In April 2010, after a 93-year relationship, GM moved Chevrolet’s ad works to Publicis Worldwide.

Up until the 1960s, illustration reigned supreme in the world of Chevy advertising.

Although photography had sporadically appeared in ads since the 1920s, in most newspapers and magazines through the 1950s – which were printed on cheap paper stock and low quality presses — pen and ink drawings reproduced with greater crispness and definition than a halftone of a photograph

Illustrator Harry Borgman, former art director with the ad agency Campbell-Ewald, created a range of works for Chevy campaigns in the 1950s and 60s. The drawings “[were] very complex to do,” Borgman recalled, “as the Chevrolet engineers had to check them for accuracy. The engineers [would] go over the artwork very carefully, even counting every bar in the grill.”

Campbell-Ewald creative director Jim Hastings used a stable of designers to produce Chevy advertising throughout the 1950s. Hastings, himself a former illustrator with Patterson and Hall in San Francisco, would repeatedly call on that studio’s artists to create some of the most memorable images in the Chevy portfolio.

Stan Galli, Bruce Bomberger, Hains Hall, Gordon Brustar and Charles Allen were among the chief illustrators of the period.

Charles Allen worked at Patterson and Hall from 1950 through the 1980s, and built a reputation for remarkable craftsmanship and draftsmanship, mastering a pen and ink technique that delivered ads with great impact. Using just a series of lines, Allen could create a full range of tones, giving dimension, volume, shadow and light to emphasize the best features of a Chevy and its environment.

With the advancement of printing technology in the 1960s, illustration gave way to photography as the chief medium.

“For Economical Transportation”

In one of Chevrolet’s earliest ads, appearing in 1914– two years before its addition to the GM line – the company trumpeted how “enormous buying p ower” and “unprecedented efficiency” in manufacturing allowed it to offer “substantial financial savings” to customers.

ower” and “unprecedented efficiency” in manufacturing allowed it to offer “substantial financial savings” to customers.

That emphasis on efficiency and economy would continue long after the cars became part of the GM line.

In 1919, the automaker’s newly hired advertising agency, Campbell-Ewald, would place an all-text ad in 45 newspapers nationwide, declaring that, with Chevrolet, “The first cost is low. The upkeep is never a burden.”

By the 1950s, however, style, performance and pride in ownership became the watchwords in successive campaigns, and efficiency as a tagline took a backseat.

“Chevrolet does not think much of the possible market for the small economy car,” said Chevrolet general manager Edward Cole in 1958. Thirteen years later, Chevy would boast of manufacturing “the biggest Chevrolets ever.”

With the gas crisis of the 1970s, fuel economy became a major concern, “MPG” became a household phrase and Chevy finally responded with down-sized cars; as the advertising stated, “We made it right for the times without making it wrong for the people.”

Chevy and the Great Depression

In 1929, the American economy plummeted — and the Great Depression ensued.

Despite the nation’s continuing financial woes, Chevrolet rolled out its 1932 models with a mammoth sales promotion drive, including 25,000 outdoor boards, ads in 5,355 newspapers, radio spots on 169 stations, window displays at 10,000 dealerships and more than 1 million lapel buttons distributed by dealers.

The company even mailed a four-inch phonograph record to every owner of a Chevrolet, offering “advance information on the great American value for 1932.”

Chevrolet’s 1932 sales plunged 44% — while the industry fell 43%. Yet, by the next year, with its unwavering push of a value message, touting cars “at a price which takes into account today’s incomes,” Chevy’s market share would rise to one-third of all US car sales.

Chevy in War Time

The onset of World War II would bring civilian auto manufacturing to a halt, as factories shifted to military production. In an effort to keep the brand alive, Chevrolet in the 1940s promoted programs emphasizing car conservation, mileage rationing, observation of speed limits to reduce gas consumption and carpooling.

“Save the wheels that serve America” became a recurring slogan.

At the war’s end, with production ramping up, Chevy ran newspaper ads in 4,000 cities with the message, “Thank you for waiting for delivery of your new Chevrolet.”

The post-war ads promised that “patience will be more than rewarded when we hand you the keys to your new Chevrolet, for here, in our judgment, is the first and only automobile to bring you big car quality at low car cost.”

Women Drivers

Women have long played a key role in deciding household purchases, and early on Chevrolet recognized their importance in the automobile buying process.

One of the first campaigns in the auto industry targeted exclusively at women was launched by Chevy in 1947, with ads — stressing safety, convenience and family togetherness — placed in Ladies’ Home Journal and other popular women’s magazines.

Chevy would extend the reach of its women’s campaign in 1960, with a unique cross-promotion in which clothier Smoler Bros. produced dresses color-coordinated to match Chevrolet’s new line of cars. Dresses were promoted in department stores nationwide. Women were encouraged to submit their reason for liking the Chevy-shade clothes. The winner, predictably, received a new Chevrolet.

Horsepower Races

Chevrolet performance in the late 1950s was legendary. Yet reckless driving at high speeds prompted Congress in 1957 to attack what was called the “horsepower race,” believing that competitive performance levels among American manufacturers were responsible for mounting, lethal accidents.

Automakers voluntarily pledged not to emphasize speed in their advertising – and to stop using racing results in their marketing efforts – but the pledges faded by 1962 with the dawn of the muscle-car era.

Chevy advertising again would be affected by Congress when consumer crusader Ralph Nadar’s 1965 publication, Unsafe at Any Speed, singled out the Chevy Corvair for harsh criticism.

Chevrolet was ordered to stop promoting speed in their advertising, leading the automaker to pursue creative ways to display performance — without displaying performance.

Chevrolet was ordered to stop promoting speed in their advertising, leading the automaker to pursue creative ways to display performance — without displaying performance.

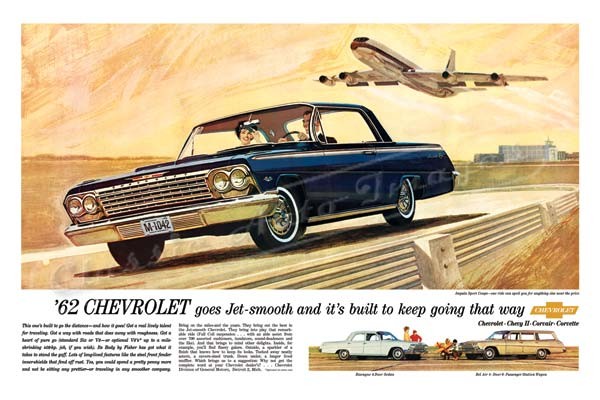

Jet Smooth

Credit for the distinctive tailfins on the 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air goes to General Motors design chief Harley Earl, who claimed his inspiration came from the twin-tailed P-38 Lightning fighter plane of World War II.

As jet-powered aircraft climbed in commercial use in the late 1950s, the fins grew in proportion, reaching new heights and lengths – with design features pushed to even more futuristic levels with the dawn of the space age in 1958.

Cars soon became “spaceships for travel on Earth.”

Chevy would capitalize on jet travel being less choppy than previous propeller planes – and tie itself to modern travel — with the theme “Jet Smooth,” coined by Ted Little, chairman of the board at the ad agency Campbell-Ewald.

Chevy would capitalize on jet travel being less choppy than previous propeller planes – and tie itself to modern travel — with the theme “Jet Smooth,” coined by Ted Little, chairman of the board at the ad agency Campbell-Ewald.

The Freedom of the Open Road

In 1949, composers Leo Corday and Leon Carr penned a tune called “See the USA in You Chevrolet.” Soon, an advertising jingle became the soundtrack for millions of motorists headed for the open road in post-World War II America.

In 1956, the US Congress would pass the Federal Aid Highway Act, accelerating cross-country movement with the authorization of tens of thousands of miles of highways connecting more than 200 cities nationwide.

Ribbons of blacktop replaced rutted dirt roads and brought a new sense of mobility to people from coast to coast. Chevrolet seized upon the possibilities with a continuing campaign that played on the freedom to drive wherever desired – and the pride of driving American to see America.

Chevy on the Telly

In 1948, Chevrolet ran its first national television commercial – despite the fact that just 0.4% of US homes had a set.

Chevy was the first auto manufacturer to truly recognize the potential of the medium, and in 1949 would broaden its broadcast presence with the sponsorship of a new, albeit short-lived CBS TV series, “Inside USA with Chevrolet.”

By 1950, nearly 10% of households had a TV, and Chevrolet further expanded its TV placement for its new campaign, “America’s best seller, America’s best buy.” It was “an innovation,” Ad Age reported at the time, “in widespread use of television.”

The following year, Chevrolet signed a deal to sponsor entertainer Dinah Shore’s NBC TV shows. Begun in 1951, the shows quickly evolved into a weekly variety program entitled “The Dinah Shore Chevy Show.” Shore ended each show with the singing of “See the USA in Your Chevrolet” to a national TV audience – one that, by 1954, encompassed half of all households in the US.

In 1961, Chevy would drop its sponsorship of “The Dinah Shore Show” and shift its advertising money to the hit TV western, “Bonanza.”

Discussion

No comments yet.